VIRGINIA GORDON

Communications Coordinator

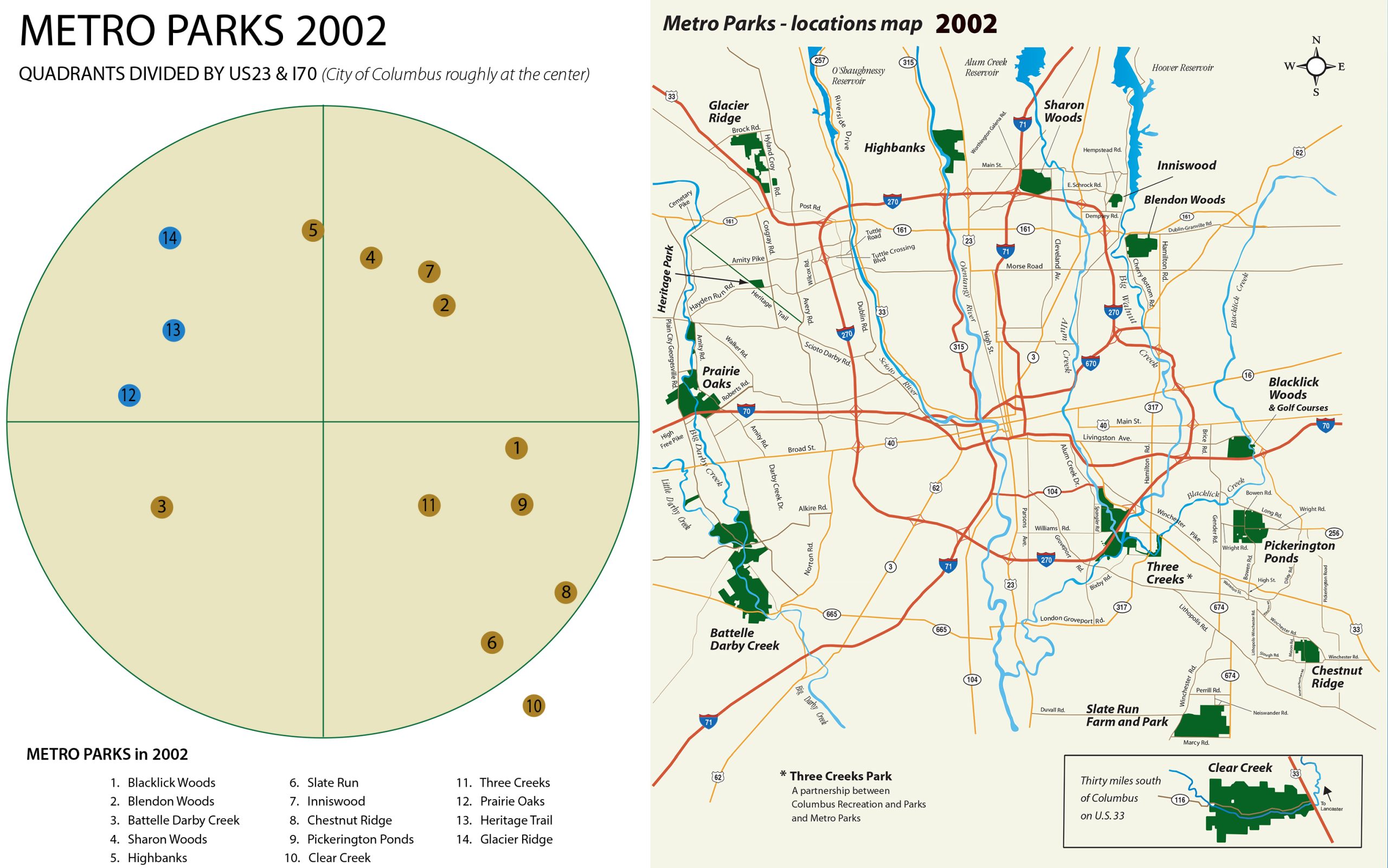

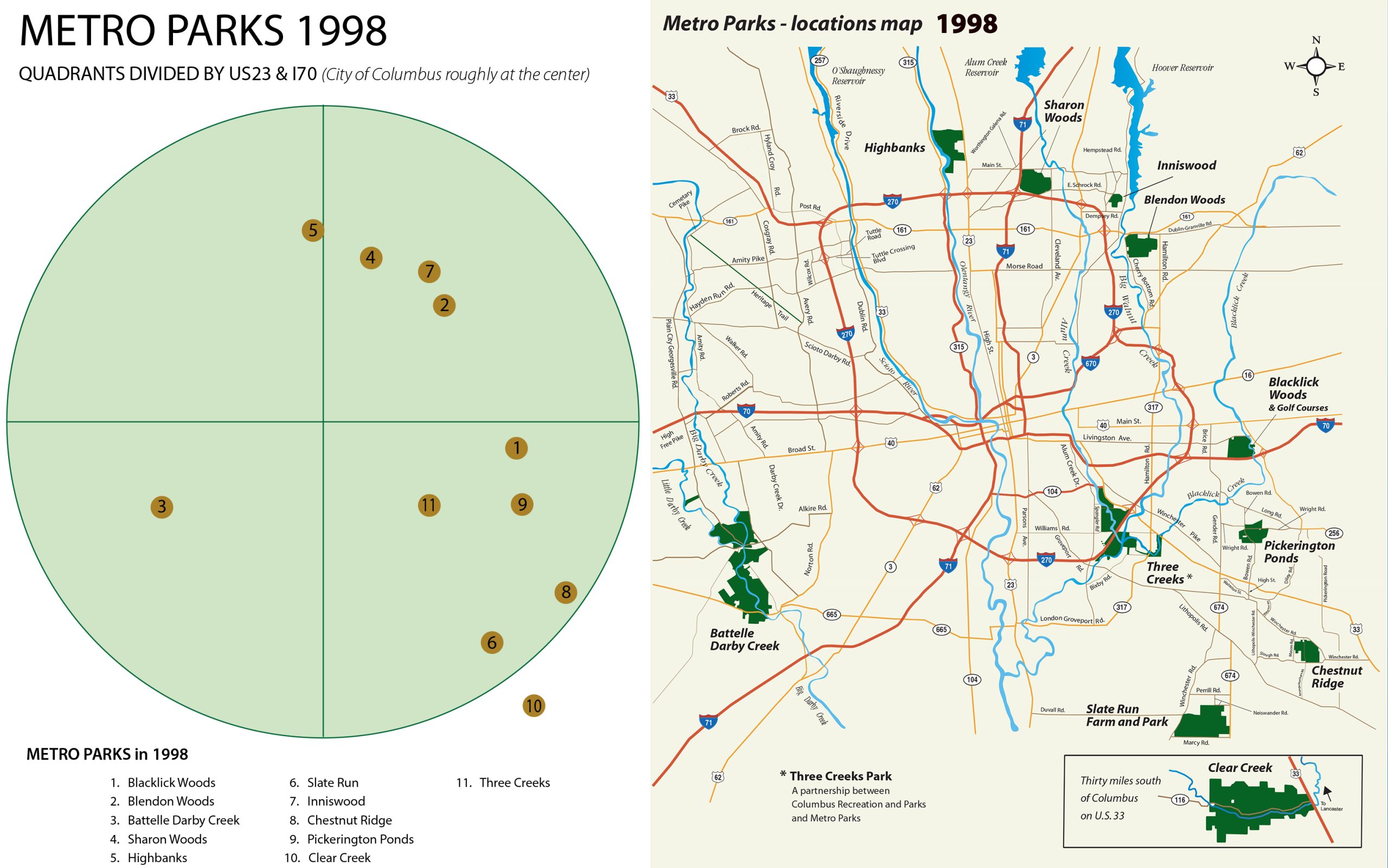

As the 20th century entered its dotage, the map of Metro Parks’ locations showed a distinct lack of presence in the northwest. There were 11 Metro Parks in 1998, totalling a little over 16,000 acres in area. Seen as a circle with the city of Columbus at its center, the northwest quadrant lay almost empty. Highbanks Metro Park touches the boundary of the quadrant, as its eastern border is bounded by US23 (represented roughly by the north-south line of the graphic below), but the rest of the quadrant was empty. The southwest quadrant had only one park, but this was Battelle Darby Creek, already more than 3,500 acres in size before the millennium, and which would continue to grow to twice that size during the first two decades of the 21st century. The other nine parks were located on the east side of the divide.

THE NORTHWEST PARK (GLACIER RIDGE METRO PARK)

Metro Parks planners had begun to talk about a Northwest Park as early as 1995. This was separate to a plan already in place to open Prairie Oaks Metro Park (the 12th Metro Park), located in the southern section of this northwest quadrant (see 20 IN 22: The Millennium Parks). After numerous indepth discussions with representatives from the City of Dublin, Union County and Jerome Township, Metro Parks drafted a Memorandum of Understanding, highlighting the principles of an agreement to open a new Metro Park in Jerome Township. It was signed by all the parties to the agreement in December 1997. As part of this ‘initial’ agreement, (and subject to the availability of funds), Metro Parks promised to commit $7 million for land acquisition and park development through the year 2010, and the City of Dublin committed to provide $5 million for land acquisition during the same time period. Title to all property acquired for the park was to be held by Metro Parks as the sole owner.

Metro Parks included its commitment to open a Northwest Park in its promises while drafting its Levy proposals, due to go to the voters of Franklin County in May 1999. After passage of the Levy, land acquisition began in earnest. The initial plan had envisaged land purchases of between 800 and 1,000 acres, targeted south of Mitchell-DeWitt road (see MAP). Emphasis was placed on acquiring large contiguous areas of land. As negotiations began with local landowners, it was discovered that a lot more land was available north of Mitchell-DeWitt Road, all the way up to Brock Road. The anticipated northern park boundary shifted north, but the desire for land in the southern section of the original targeted area remained strong, as the soil types there showed the land to be ideal for wetland restoration.

As a result, the 933 acres of land acquired up to the end of the year 2000 was in two distinct and disconnected portions, north and south. The focus of Metro Parks’ land acquisition efforts changed and smaller land parcels were sought to link these two sections together. By the end of 2001, this objective had been achieved.

PLANS AND CONSULTATION

An Advisory Group was constituted in February 2000, to oversee the planning process for the new park. The 15 members of the advisory group included community volunteers along with representatives from the City of Dublin, Union County’s Soil and Water Conservation District and Engineering departments, and Metro Parks. Three concept plans were developed and were presented as consultation documents at public meetings held at various Dublin locations in September of that year. Using feedback from those consultations, Metro Parks produced a Conceptual Master Plan, which was unveiled at a public meeting at Dublin Recreation Center in January 2001. The Master Plan envisaged a park with nature trails, a bridle trail, a picnic area, and restored wetlands.

The successful land acquisition, and the wide community endorsement of the proposed park, inspired Metro Parks (rising to $17 million) and the City of Dublin (rising to $7.7 million) to increase their financial commitments to the Northwest Park.

THE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN

Most of the land in the new park had been used for agriculture, but there were a few scattered, yet mature, second-growth woodlands. Second-growth woodlands are forest areas that have recovered after having been completely cleared for timber harvesting or agricultural purposes. In the central area of the park, between Mitchell DeWitt Road and McKitrick Road, there were three such woodlands between two and three acres in area. Resource Managers proposed and eventually began a long-term reforestation plan to connect and expand these areas to about 50 acres. There are also some additional second-growth woods in the northern area of the park, which were also marked for expansion. The new woodlots were planted with beech, oak, hickory and maple trees.

The initial Resource Management Plan also contemplated the establishment of about 170 acres of grasslands in the northern section of the park. Plans for a restored wetland in the southern section of the park were given a massive boost when Honda of America Mfg announced, in December 2000, that it would donate $500,000 over a 3-year period to establish a “premiere education site” in the proposed 200-acre wetland site.

THE PARK WITH NO NAME

For years, ever since the Memorandum of Understanding had been drafted, partners in the project referred to the new park by its codename, the Northwest Park. As the new park began to take shape, with trails, wetland cells, access roads, picnic shelter and playfields, restrooms and lots of resource management enhancements becoming ever more advanced, an opening date in September 2002 became feasible. But what would the park be called?

The Advisory Group had put forward a great many naming ideas for discussion. Among the favorites were Indian Run Metro Park, Coyote Hills Metro Park, White Oak Metro Park and Pheasant Run Metro Park. But the chosen name, of Glacier Ridge Metro Park, came from Advisory Group member Charlie Bynner. “The main thing I considered is the terrain up here” said Bynner, who owned 60 acres near the park. “We’re on the spot where the last glacier retreated and left a deposit of sand and gravel. The features are really unique to this area.” Bynner’s idea was supported by another Advisory Group member, Carroll Fogle. “You can really see how the land is fairly flat until you get past Mitchell-DeWitt Road,” Fogle said. “Then it tries to take off as it goes north and turns into a ridge.”

Brynner’s suggestion was accepted by the Board of Park Commissioners, and the Northwest Park now had its name. Glacier Ridge Metro Park opened with a grand public celebration on September 22, 2002. It became the 14th Metro Park. Prairie Oaks Metro Park had opened in 2001 and the small, 87-acre Heritage Trail Park, a partnership between Metro Parks and the City of Hilliard, in support of Metro Parks’ management of parts of the 6-mile Heritage Rail Trail, had opened earlier in 2002.

A DETOUR TO THE HERITAGE TRAIL

The Heritage Rail-Trail Coalition was founded in 1992 with a mission to support efforts to acquire land on an abandoned railroad corridor, which had ceased operating as a railroad back in 1984, and to convert the land into a trail to connect communities in the area between Hilliard and Plain City. A local businessman, who had bought 11 acres of land from Conrail in 1985, sold 10 acres of this to the City of Hilliard. The coalition sought to buy another 50 acres of land direct from Conrail, but were given only six months to raise the necessary $60,000 asking price.

Early partners in the coalition included the City of Hilliard and both Washington and Norwich Townships, along with the Hilliard Chamber of Commerce, with support also from Metro Parks. Thanks to great community support the Coalition achieved its fundraising aim, with about a third of the money coming from The Columbus Foundation.

Hilliard paved the first section of the new Heritage Rail Trail, about 1.3 miles starting in Old Hilliard and heading northwest to The Homestead, then a Washington Township Park (which is now Homestead Park). This section of the new trail was officially opened with a ribbon-cutting ceremony in May 1995. The Coalition donated the next section of trail to Hilliard in 1996, continuing northwest to Hayden Run Road. This section was also paved by Hilliard and opened with another ribbon-cutting ceremony in 1997.

HERITAGE TRAIL BECOMES THE 13TH METRO PARK AND A NEW BRIDLE TRAIL

In 1999, the Rail-Trail Coalition donated the remaining section of railroad corridor land to Metro Parks. This stretch, from Hayden Run Road northwest to Cemetery Pike, runs for just beyond 3.6 miles. As well as paving this expanse of the Heritage Trail, Metro Parks also set out to lay a bridle trail, running parallel with the paved trail all the way to its termination point at Cemetery Pike. Metro Parks wanted to provide a staging area for the bridle trail and bought 49 acres of land from the Columbus Southern Power Company in 1999, to form part of a new Metro Park. The Rail-Trail Coalition gifted another 34-acre tranche of adjacent land to Metro Parks, and other small acquisitions led to a total area of 87 acres for the Heritage Trail Metro Park. It opened as the 13th Metro Park in spring 2002, along with the extension of the Heritage Trail and dedication of the new Bridle Trail. The staging area includes horse-trailer parking and a corral for the horses. The Bridle Trail is surfaced with sand and gravel and runs along the east side of the Heritage Trail as far as Amity Pike, where it crosses over the the west side for the remainder of its run to Cemetery Pike. A desire to extend the Heritage Trail a further mile or so to Plain City is on a long-term wish list, but opportunities to purchase the additional land needed to meet this objective have so far not materialized.

Heritage Trail Metro Park also includes a fenced 4-acre dog park, operated jointly by Metro Parks and the City of Hilliard. The dog park has separate areas for active and less active dogs. It includes a splash and sprinkle water pad, ideal for your dog on hot days, just to have fun in or take a drink, plus an exercise tunnel and other activity equipment.

MORE ABOUT THE RIDGE

The ‘ridge’ within Glacier Ridge Metro Park is a subtle and gentle rise of about 100 feet, heading north from the wetlands to the northern boundary at Brock Road. The rise is most easily noticed if viewing the park from State Route 33. It’s part of the natural topography of the park and is the result of glacial deposits when the last glacier in Ohio, the Wisconsin Glacier, retreated from central Ohio about 15,000 years ago. The park sits on the Powell Moraine, one of numerous bands of east to west glacial deposits of sand, gravel, and boulders left by the retreating, or melting, glacier. A recessional moraine, like the Powell Moraine, consists of a secondary terminal moraine deposited during a temporary glacial standstill. Such deposits reveal the history of glacial retreats. The advancing Wisconsin Glacier had first reached central Ohio about 22,000 years ago. It continued to southern Ohio before finally starting to retreat.

EARLY PARK DEVELOPMENTS

The 988-acre Glacier Ridge Metro Park opened on September 22, 2002 (the current acreage has risen to 1,032). At the time, only the northern section of the park was open to the public, and included a 3-mile bridle trail, a picnic shelter, a nature trail, and 2.5-mile paved multiuse trail that looped around the first phase of restored grasslands. Developments moved quickly. The bridle trail was extended to 5 miles, and named the Savannah Trail. A staging area and small arena for riders was built adjacent to the bridle trail. A new multiuse trail, the 2.8-mile Ironweed Trail, was opened in 2004 and connected the northern section of the park with the wetlands, in the south. An 18-hole disc golf course was created. Players must bring their own discs, but can play the course free throughout the year.

THE WETLANDS

The 200-acre wetlands at Glacier Ridge have developed into wonderful habitat for shorebirds, wading birds and waterfowl, plus many other species of wildlife. At the heart of the wetlands, the Honda Wetland Education Center, which opened in 2005, has proven to be a great educational resource for students. Partly funded by a grant of $500,000 from Honda of America Mfg, the Education Center includes an open pavilion as a program space, with interpretive displays and restrooms. The Center’s main building is a timber frame barn, built before 1850 and relocated from McKitrick Road and rebuilt on site. The Center is located on one of the wetland cells, with a spotting scope for closeup views of wildlife. A boardwalk extends 1,000 feet through the wetlands, and a nearby observation tower, 25 feet high, provides a great overview of the entire wetland site.

GREEN ENERGY

After a local farmer made an offer to donate a wind turbine to Metro Parks, the park district worked with Green Energy Ohio to make ‘green’ energy an educational focus for Glacier Ridge. A 120-foot tower and a 10kW wind turbine were erected in the northern part of the park soon after the park opened. A couple of years later a solar-powered photovoltaic array was also installed, and it became part of the new park’s Wind and Solar Learning Center, which was used on school-group visits to teach about alternative energy sources.

LATER PARK DEVELOPMENTS

Building on the success of the Obstacle Course at Scioto Audubon Metro Park, Glacier Ridge opened its own 3-acre Challenge Course in 2018. The course features 12 challenging stations, which include a large cargo net for climbing, tubes to crawl through, logs to shimmy under or scramble over, a rope climb and acrobatic rings. It is surrounded by a half-mile loop trail.

Close by, a natural play area features cedar structures with towers, ramps, ropes, ladders and a zipline. It was designed with kids in mind and was built by students from the Ohio State University Knowlton School of Architecture. Also in 2018, the park opened a 2.5-acre Dog Park. It’s designed for dogs of all sizes and features an open field, drinking fountains, a paved path and a wooded area for dogs to explore.

MAP OF GLACIER RIDGE METRO PARK

HOMESTEAD METRO PARK

Homestead Metro Park is unique, amongst the 20 Metro Parks, in that it existed as a park before it became the 18th Columbus & Franklin County Metro Park in September 2015. The Homestead, a 44-acre park in Hilliard, opened in 1992 and was a Washington Township park.

The Washington Township Trustees acquired the land in 1990 and were supported by Brown Township and Norwich Township in a mission to create a park for families to enjoy and to provide a historic monument to Midwestern rural agricultural life. The land was amongst the parcels of land granted to state troops of the Continental Army that served during the Revolutionary War. From the beginning, the land was used for agriculture. Because the park was adjacent to the Heritage Trail, created on an abandoned railroad line, a “railroad” theme was also adopted for the park.

The railroad theme continues to this day, and includes the Norwich Junction, a replica train station and rail platform, and an adjacent caboose (a railroad car coupled to a freight train, which was used by the train crew). The caboose was donated to The Homestead by Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) in 1998. Conrail had been the operator of the since abandoned railroad line on which the Heritage Trail was built. In a different area of the park, and on the boundary with the Heritage Trail, a replica was built of a train depot that had once been located on the line near Hayden Run Road. The replica depot was named ‘Bradley Station’ by Brown Township Trustees, to honor local historian Ray Bradley.

The park was very successful and popular with local residents. Educational programs were offered, and prominent features included a 2.5-acre fishing lake, various reservable picnic shelters, a paved trail, courts for sand volleyball and basketball. All was going well until 2013, when it was discovered that the park’s water supply, from onsite wells, showed signs of contamination. A new water supply was necessary. An agreement was made with the City of Hilliard, to annex the land and provide water service to it. The Washington Township board of trustees faced some difficult discussions about the expense of operating and maintaining its parks, and in 2014 announced its intention to dissolve the township’s Parks and Recreation Department. The City of Dublin took over ownership and management of Ted Kaltenbach Park, while the township entered into discussions with the City of Hilliard and with Metro Parks about the transfer of ownership of The Homestead.

It was agreed that Columbus & Franklin County Metro Parks was the best fit for the future of The Homestead. The Township trustees and the Metro Parks board of commissioners approved resolutions for the transfer in June 2015. As part of the agreement, The Homestead was deeded to Metro Parks at no fee. Washington Township said that the money saved by foregoing the operation and management of the parks would allow it to focus on its core mission of providing fire suppression and EMS support to the township and to the City of Dublin.

On September 1, 2015, Homestead Metro Park officially became the 18th Metro Park. Metro Parks rangers began patrolling the park to ensure safety and add a friendly smile, and maintenance staff began the work of keeping the park looking at its best. Park nature programs were continued, and Homestead was added as one of the sites for Metro Parks’ popular Summer Adventure Camps. The shelters continued to be offered as reservable facilities.

For 2025, Metro Parks has allocated a million dollars from its capital improvements budget to give Homestead a makeover which will result in better vehicle movement and parking, additional restrooms and shelters, plus resurfaced and upgraded trails and a better connection to the adjacent Heritage Trail.

What is the story of the white building shown in the Homestead photo please?

Hello Russ – the building in the photo was the main office for Washington Township’s Parks and Recreation Department and was also used as a garage for parks and recreation vehicles. It is used by Metro Parks as a naturalist office.