ANDREW BOOSE

Aquatic Ecologist

Great Southern Metro Park is a future park and a key piece of park land that will aid in connecting Scioto Grove with the Metro Parks Greenways. The park lies east of local businesses along South High Street in, with I-270 to the South and a quarry to the west. This article contains photographs and information obtained from private property and areas of the future Great Southern Metro Park.

As of late there has been much ado about quarries in the Metro Parks. The exposed rocks in these quarries at Great Southern formed millions of years ago while some rock formed a mere decade or less ago. Limestone dating back to the Devonion era is the oldest. On top of the limestone lies layers of various rocks scraped up by the glaciers and left behind as they melted. And then there are the rare rocks being formed a centimeter or less a year in the form of tufa. Scott and Cheryl Brockman graciously spent a couple of hours with Metro Parks Staff to give us an in-depth look at the rocking and rolling history of what lies beneath some of your Metro Parks. Scott is a retired geologist of the State of Ohio.

Metro Parks on the western side of Franklin County lay on top of limestone that is millions of years old, formed from the sediments of long-gone seas that once covered the land. It is not uncommon to find an array of fossils in the limestone, including brachiopods, trilobites, bryozoans, mollusks and corals. These fossils can be found in the sections of limestone cleaved off during quarrying activities, some of these can be regularly found just kicking around a pile of limestone gravel.

Well after the seas receded, the earth cooled and glaciers made their slow march from the north, covering the land in ice up to a mile thick. The glaciers scraped rock from Canada and pushed it slowly south. This is why rocks such as granite, gabbro, gneiss and schist, in pieces ranging from sand size particles to boulders known as glacial erratics —the size of automobiles— can be found through the glaciated portion of the Metro Parks.

THE CHASM AT GREAT SOUTHERN

In an area that is currently inaccessible to the public, in Great Southern Metro Park, recent flood waters scoured a chasm that revealed out about 17,000 years of glacial and human history in the matter of hours. The flood left behind a rare if not one-off occurrence for Metro Parks. Quarrying activity adjacent to Great Southern has left a large deep hole in the earth. The flood that created the chasm washed out a retention pond. The gush of water washed soil and rock from above the quarry into the bottom of the quarry pit another 100 or more feet below. What is left behind is a well-defined display of layers of cobbles, pebbles, sand and mud from the last glacial period, to the feeder canal built in the early 1800s that connected Columbus and Lockbourne, to present day development.

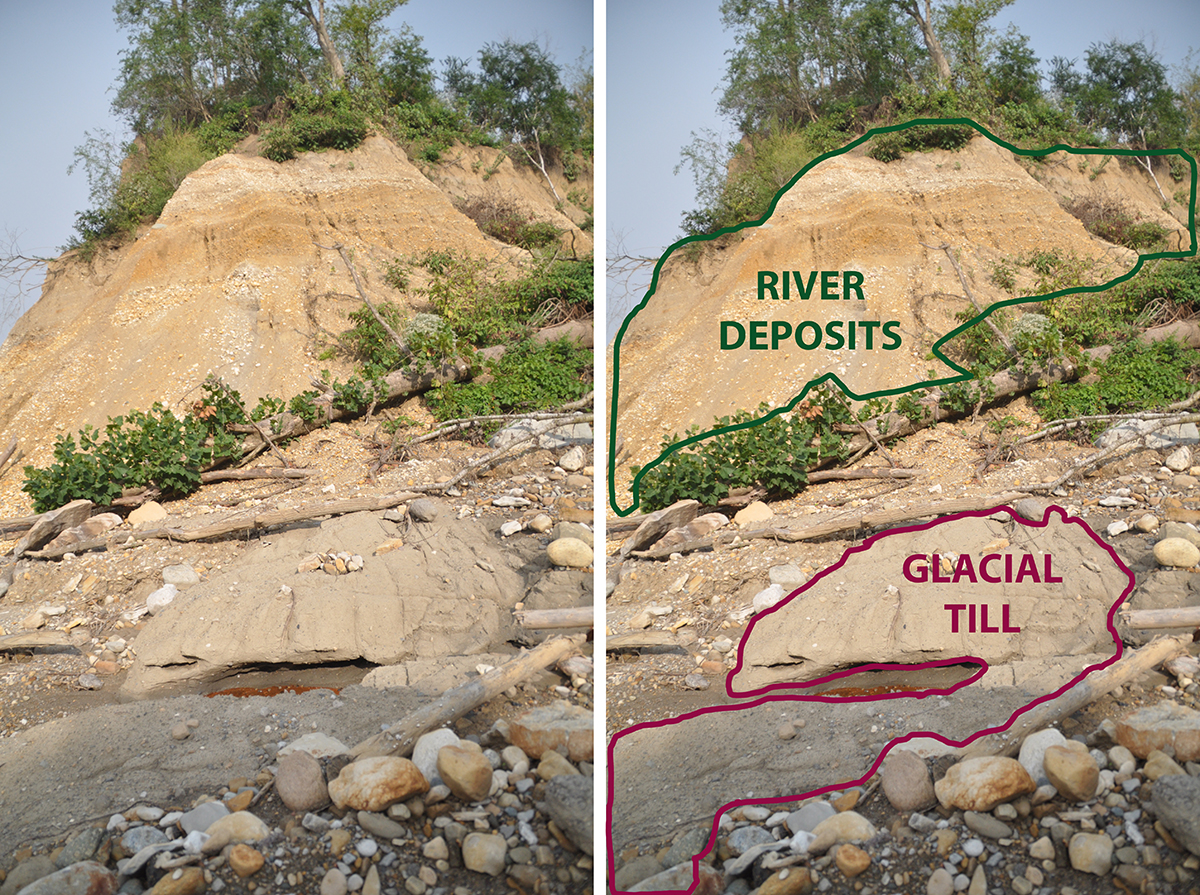

At the bottom of the chasm is mud from a lake most likely formed when a bend in the river was isolated from the flow and formed an oxbow. Thousands of years old coniferous woody debris and other unidentified woody material were exposed in the fine, silty, dark grey mud in the bottom of the ancient lake. Snail shells were also abundant in the mud. In places glacial till covers the mud with its fine sand and gravel that sifted down through the glaciers in the melt water. Directly above these layers are alternating bands of sand and cobble denoting times when slow-moving water and fast-moving water events occurred. The finer sediments were deposited from slower-moving stream channels while faster-moving stream channels deposited larger gravel. This same action can be seen in just about every moving stream in your Metro Parks.

Another interesting find are familiar fresh water mussel shells intermixed in the sand and gravel layers, showing the existence of these mollusks occurring thousands of years ago. Above the sand and cobble layers lies a layer of soil, depicting a time in which the river no longer flowed there and the lake had silted in. The grey lower soil turns browner over time as organic materials slowly leach downward. Above, the roots of modern-day plants penetrate the most recently formed soil. Also laying on the top of the soil is a thin layer of sand and gravel, remnants of the feeder canal still visible in areas. The feeder canal was last used around 1914.

So, as you stroll through your favorite park, take a moment to consider the rock and roll history of your Metro Parks and behold what may be a million years of history held in the palm of your hand.

Great article Andrew!

New parks are so fascinating to watch unfold.

where is Great Southern?

Great Southern is an area on the south side of Columbus. The future park area is closed to the public and will be developed in the coming years.

Very interesting post, I’m glad I came here.

Columbus metro parks are crushing it! thanks.