OLIVIA GARAS

Resource Management, North End Land Management Coordinator

We are all familiar with the crisp cold air, blanket of snow and icy roadways that winter months in Ohio bring us. The crunch underfoot as we walk to and from our cars and homes is something we recognize as the “as-salt” of winter in all of its glory! Certainly, at Metro Parks, we think about spreading salt, most often as something we must do to keep the public safe. What we don’t always think about is what happens to that salt after we spread it in our parks. Wise use of our road salt can mitigate negative impacts to our natural environment, like soil and watersheds.

Salt, or sodium chloride, is a mineral that is found in many forms from table salt, like what we season our turkey with, to rock salt, which is most often used as ice melt on the roads. Once it’s on the roadway and has done its job, what happens to it? Where does it go? Like many things that are on the surface of the ground, salt moves with rainfall and snowmelt into the soil and towards waterways as runoff. Unfortunately, salt doesn’t break down and after it runs off it can contaminate waterways over time due to its persistence. This can be really bad news for native plants and wildlife that rely on these types of ecosystems to survive.

Why is salt an environmental, and public health problem?

Salt is a naturally occurring mineral that is essential to many types of organisms, including ourselves. However, too much salt can result in ill effects. Just think back to all the “low sodium” options at the supermarket when we have had a bit too much in our diet. The same can be said for aquatic and terrestrial wildlife. The difference is, they don’t have “low sodium” options. The waterways and other ecosystems they call home are all they have to survive, and many species are very sensitive to salinity changes in the environment. When we use more than we need to on the roads, it all goes into the water and soils. This can pose a real problem to biodiversity as high salt content can damage ecosystems and wipe out sensitive species. This can throw off the natural balance that ecosystems need to thrive.

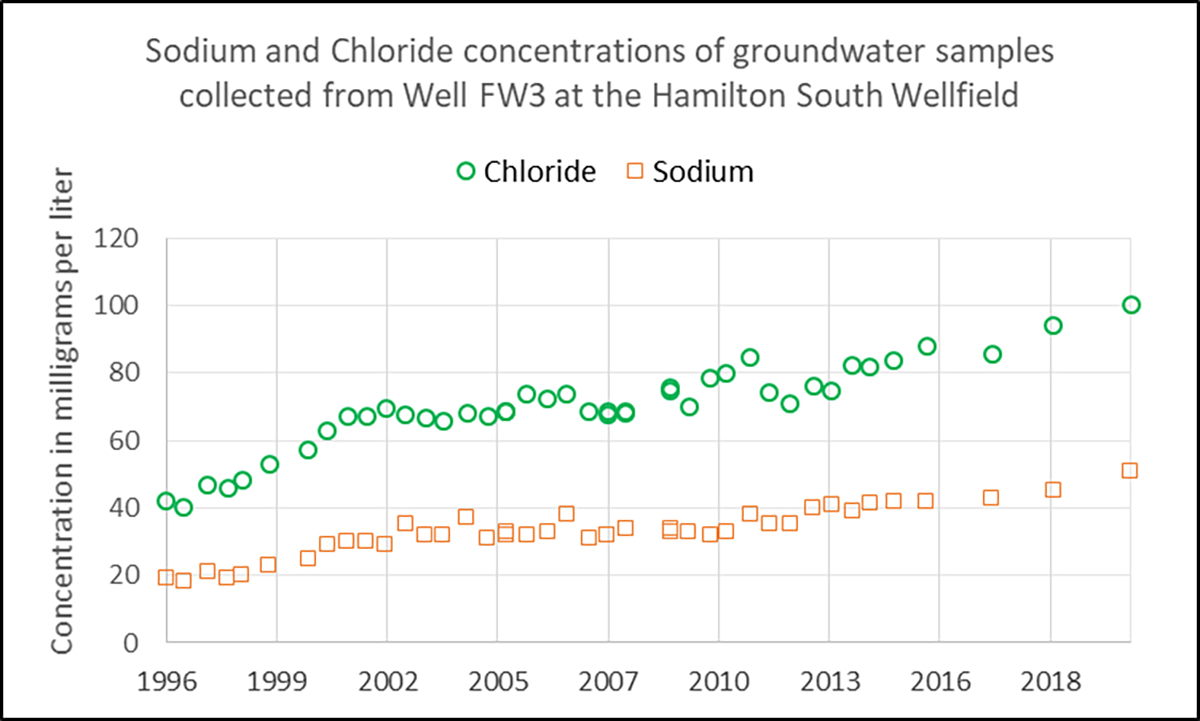

In addition to the damage to biodiversity, the presence of salt in any waterway can reach the water we drink as well. Long term trends for salt content in waterways has been monitored over time in southwest Ohio by the Ohio EPA, Miami Conservancy district, US Geological Society, and the Hamilton to New Baltimore Groundwater Consortium. They have found that of the 70 wells they have surveyed, 39 of them have shown signs of increased salt content since the 1990s.

This is a real problem when it comes to drinking water due to the corrosive tendencies of salt to metals. High chloride content can break down pipes and pumps that are used to deliver drinking water and expose other materials found in them, such as lead. Perhaps I should have “lead” with that!

This understanding has partially been attributed to the lead found in the drinking water in Flint, Michigan. The city changed its source of water from the Detroit Water and Sewage Department to the Flint River. Chloride levels sampled from the Flint River were much higher than the previous water source, which partially caused the corrosion and lead poisoning.

Increase in salt use

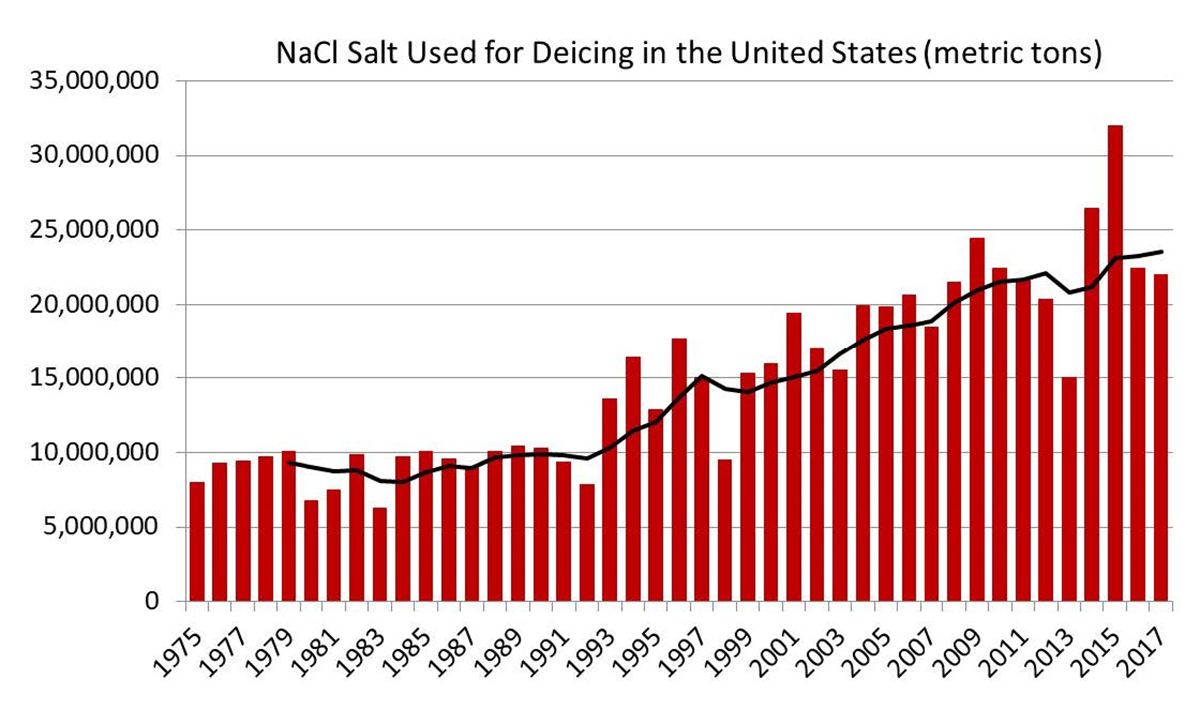

Road salt is not the only thing to blame. These higher levels of chloride in water can also be attributed to water softeners, agricultural fertilizers, and natural elements such as the breakdown of soils, rocks and minerals. That fact should be taken “with a grain of salt,” however, as our use of road salt has increased significantly over time. We have gone from using 8 million metric tons in the 1970s, to using more than 20 million metric tons in recent years in the US. In Ohio alone, from 2019-2020, we used approximately 385,000 metric tons of salt! Talk about “shaking” it up!

How can we be good stewards of the land we manage?

The use of salt in our parks is essential to maintain safe travel for visitors and employees, that is our responsibility as a park system. It is also our responsibility to contribute to these above stated issues as little as we possibly can, for our visitors, ourselves, and for other important organisms. Plowing and shoveling snow is common practice for our district, as a first line of defense.

Getting the “scoop” on de-icers can greatly benefit what we do, especially when we want to be using it efficiently. Salt is most effective on ice, decreasing its use means using other means of removal first, like shoveling or plowing. Although salt helps with snow melt it does not have the ability to completely remove snow, like a shovel does. In the spirit of using less salt, it should not be applied to snow or dry pavement. Reading the labels and only using de-icers in recommended temperatures is also a good “granule” of information, and avoid use when temperatures are below that recommendation. It’s important to keep in mind, overuse of salt does not equate to increased safety or effectiveness, it only results in waste, contamination and increase of costs. No matter the impact salt has, we can also save money when we use less. It is recommended to use just enough to cover the pavement with a 2- to 3-inch space between granules, this is good to remember when hand spreading an area, and when calibrating salt spreaders.

For more information on recommended uses of salt for snow melt practices, visit the Franklin County Soil and Water website

Thank you for this informative article. I would add that salt alternatives are used in other cities. Residents are largely not responsible for the overuse of salt; municipal governments are. What do the major cities in Ohio use? How are Metro Parks and/or other impacted groups educating and advocating for lowering the use of salt, either by using it more conservatively and correctly or using alternatives?

Don’t they use beet juice as an alternative for mild ice on roads?

Beet juice is essentially an aid to salt brine use, it is mixed with brine and used in certain applications with a rate of about 80% brine and 20% juice. This does help when we are talking about large scale snow removal operations, but it is very rarely used completely on its own. Special equipment is required to be able to spread liquid solutions, and this is not something the Metro Parks are equipped with. This is an expensive transition when all our parks are fully prepared to spread salt. There are other states that use beet juice more frequently, but Ohio is a large producer of salt and the convenience of its availability in this state has often outweighed the cost of transitioning out of using it. The best way to be environmentally conscious with the materials we have access to are to use only what is necessary in a given application, and to overall be mindful of our impacts. I hope that eventually we can phase into even more environmentally-friendly practices as a state in general, but it will take baby steps. Thank you so much for your interest! — Olivia Garas