VIRGINIA GORDON

Communications Coordinator

In music, critics speak reverently of the Three Bs (Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms) and their prominent role in the history of music and the arts. The history of Clear Creek Metro Park also has a strong connection with its own Three Bs, the Becks, the Benuas and the Barnebeys. All three families had deep connections with the land in the Clear Creek Valley, land which today forms major portions of the second-largest of the 20 Metro Parks, Clear Creek Metro Park.

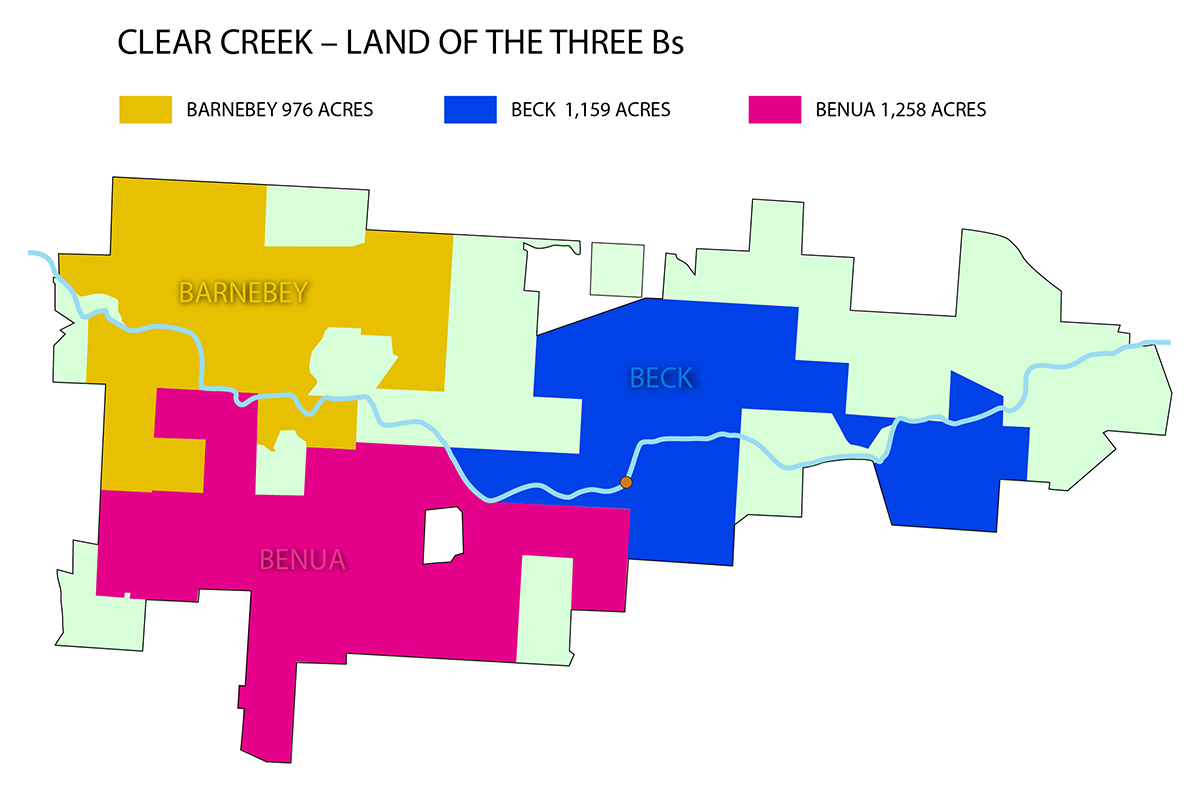

The map superimposes the lands formerly connected with the Becks, the Benuas and the Barnebeys over the current Clear Creek Metro Park boundaries. The brown dot on the creek marks the approximate location of the planned Logan Dam at the 3.1-mile point.

A PLAN TO FLOOD THE VALLEY

In 1973, when the children of Allen F. Beck gifted 1,159 acres of their father’s land to Metro Parks, the natural habitat of the Clear Creek Valley, forged over millennia of geological imprints, lay under threat. Four years earlier, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had published a proposal to build a flood control impoundment about 3.1 miles upstream from the confluence of Clear Creek with the Hocking River. The dam would have been built on land then owned by Mr. Beck. If it had been built, the so-designated Logan Dam and Reservoir would have flooded some of the most beautiful areas of the Clear Creek Valley upstream of the dam.

THE PRIMACY OF THE LAND

The Becks opposed the proposal. Of course they did. And so did many other landowners in the Clear Creek Valley. And so did conservationists, naturalists, environmentalists. As proposed, the dam was slated to achieve the Army Corps of Engineers major declared purpose, to reduce flooding along the Hocking River Valley and to supply water to the city of Lancaster for municipal and industrial use. As a by-product, the reservoir thus created upstream would provide what the engineers declared to be “much-needed water recreation facilities for the area.” A serious consequence, as acknowledged in the Army Corps of Engineers own report, was that the success of the reservoir as a water recreational facility would lead to commercial or residential developments that would have “drastically altered or generally destroyed the present desirable aspects of the environment downstream of the dam.”

So double the trouble! Destroying desirable aspects of the environment does not sit well with anyone, and in an effort to mitigate this last consequence, the Engineers, having consulted with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, proposed bringing an area of around 3,800 acres of land below the dam into public ownership.

From the Army Corps of Engineers’ 1969 Report: Development of Water Resources in Appalachia: Project analyses

The construction of Logan dam and reservoir at mile 3.1 will have two distinct effects with regard to continuation of Clear Creek Valley as an area of unique scientific value. One would be the inundation of what constitutes one of the more scenic sections including a portion of an area known as “Rhododendron Hollow.” The other effect will be to accelerate substantially the rate of commercial and residential development already under way and which, soon after completion of the project, would be expected to alter drastically and destroy generally the present desirable aspects of the environment downstream of the dam.

—–Although many of the present landowners indicate their intentions to preserve their lands in a natural state, the influx of recreationists to the reservoir recreation development would have an adverse impact which would be difficult to control. Also, the lands under private ownership would not be accessible to that portion of the general public which is desirous of enjoying the very attributes which the landowners would be attempting to preserve. Heirs and/or future owners of the lands would be subject to great economic enticement to allow residential, commercial and private recreation development. These are recognized as consequential effects of project construction.

Neither the plan to flood the Clear Creek Valley, nor the palliative offer to minimize environmental damage below the dam, carried much weight with landowners, environmentalists or conservationists. Opposition was widespread and persistent.

THE BECK FOREST PRESERVE

In accepting the Beck family gift, Metro Parks acknowledged its own opposition to the dam and the obliteration of Rhododendron Hollow and other areas of natural beauty within the Clear Creek Valley. The park district willingly acceded to the Beck family’s requirement that at least three-quarters of the gifted land be dedicated as a state scenic nature preserve, which would safeguard the land from undesired development. Formal designation as a state nature preserve was approved quickly by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, and thus the Allen F. Beck Forest Preserve came to be. The designation added clout to the public arguments opposing the dam project.

The dye was cast. Yes, areas of outstanding natural beauty were going to be destroyed, but, as the Army Corps of Engineers proclaimed, at least some of the area’s need for water-based recreation activities would be addressed. They declared: “The major deficiency in the Hocking Hills Recreation Region is the lack of broad water areas suitable for water-based recreation activities. The 1,825-acre surface area of Logan Reservoir will help satisfy a portion of the area’s water-based recreation needs.”

THE NARROWS

The argument didn’t fly, or sail, or swim. Nor, ultimately, did it even hold water. Public opposition was so strong that the US Government baulked at funding the project. The Rhododendron Hollow, one of numerous such mini-valleys within the valley, was recognized as being the northwest limit in Ohio where the broadleaved evergreen great rhododendrons flourished. The hollow was contained within a larger area known as the Clear Creek Gorge, where the valley narrowed significantly. It is sometimes referred to at Clear Creek Metro Park as The Narrows. All of it would have been flooded and eliminated by the Army Corps of Engineers 3.1-mile dam and reservoir plan, which would have created a lake 10 miles long. In 1986, the Clear Creek Gorge was considered as a National Natural Landmark site. In support of the consideration, Bowling Green University Professor of Geology, Jane Forsythe, wrote:

“Clear Creek Gorge is a spectacular example of an “hourglass-shaped” valley created by the glacial blockage and reversal of a preglacial west-flowing stream. At the narrowest part of the modern valley, at the site of the old preglacial divide, the valley is exceptionally narrow, with steep rocky cliffs rising high on either side. Vegetation along the cliffs throughout the gorge is remarkably natural and not greatly disturbed.

“Although Ohio has a number (though not many) of such glacially reversed valleys, the gorge of Clear Creek is an exceptional example, because its nature and origin are so clearly evident, the narrowing of the valley is so very obvious (approaching the divide from either direction), and the rocky cliffs and associated vegetation are so little disturbed.”

Although the Beck land had been gifted to Metro Parks, and the Allen F. Beck Forest Preserve had been formally declared as a state nature preserve, it was readily understood that the establishment of an actual Metro Park lay well in the future. But the seeds had been planted. By the turn of the decade, in 1980, Metro Parks had acquired another 725 acres of land in the valley, including the famous Neotoma Valley. This 100-acre parcel had belonged to Ed Thomas, one of the foremost naturalists of his day, and one of the founding board members of Columbus and Franklin County Metro Parks.

NEOTOMA

Neotoma was the name Ed Thomas gave to the valley and to the hut he built on his property, based on the scientific name of the Allegheny woodrat (Neotoma magister). Ed and some of his scientific friends had discovered Ohio’s first recorded specimen of this species on his property. Neotoma was used for more than 40 years as a retreat for scientists as a place for study and research. Even the Army Corps of Engineers was forced to reference it in its report, declaring: “The Neotoma Valley has furnished outdoor laboratory conditions for studies associating soils physics and chemistry, plant physiology, plant pathology, effects of humidity, temperatures, air currents on animal and plant ecology as well as providing bases for solutions to earlier taxonomic problems.”

Neotoma and the other land purchases were accepted as extensions of the state’s Beck Forest Nature Preserve. The Columbus industrialist, Allen F. Beck, had begun acquiring land in the Clear Creek Valley in the 1930s. A March 1974 article in The Columbus Dispatch, extolling the family for its gift of land, not only to Metro Parks, but by extension to the citizens of central Ohio, reported that Mr Beck had planted 176,000 trees on his property over the decades.

THE BENUAS AND THE NATURE CONSERVANCY

Adjacent land, west of the Beck property, was owned by the Benua family. William Benua had been a strong opponent of the Logan Dam and Reservoir proposal. Large stretches of the Benua land would have been flooded had the project proceeded. In her will, Emily Benua gifted 662 acres of land to the state nature preserve, via the Nature Conservancy, with the express condition that the land should “forever be held as a nature preserve for scientific, educational and aesthetic purposes.” The 662 acres were formally deeded to Metro Parks in 1991. (In 1998, another 596 acres of land held by the Benua estate was purchased by Metro Parks.)

CAMP INDIANOLA AND OSU’s BARNEBEY CENTER

Our third ‘B’, Oscar L. Barnebey, was a chemical engineer who began buying land in the valley in the 1920s. His intention was to create a Church Youth Camp and in 1928 he opened what became known as Camp Indianola on a 975-acre site on the western edge of what would become Clear Creek Metro Park. Mr. Barnebey created Lake Ramona by using concrete to dam a small tributary of Clear Creek. Then he built seven cabins and a large camp lodge nearby. (It’s said that Lake Ramona was named after a well-known Columbus singer of the 1920s, Ramona Berlou.) The camp operated successfully for four decades, with various churches or church organizations taking over the day-to-day running of the camps. In 1960, after becoming unhappy with the management of the summer camps, Mr Barnebey took over direct management of the camp himself and it continued to operate successfully for a few years. As he grew older and suffered some health issues, Mr. Barnebey sought to find a benefactor who would either continue to operate the camps or commit to preservation of the land and its natural history. He entered discussions with The Ohio State University and was satisfied with their proposal for the site, which was to create an outdoor laboratory to be used for scientific field trips. Mr. Barnebey donated the land to the University and the Barnebey Center for Environmental Studies was formed. For many years, resident programs were conducted here, used by central Ohio school groups. The Barnebey Center continued to be used for biological research and for field trips throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1994, Metro Parks purchased 470 acres of the Barnebey Center property from the University, and acquired the rest of the Barnebey Center land in two separate purchases, in 1996 and then 1997. Now known as the Barnebey Hambleton Area, it is still used extensively for education, and is a very popular destination for school field trips, with programs led by Metro Parks naturalists. (James Chase Hambleton was the first President of the Columbus Audubon Society, a member of a prominent group of field naturalists, the Columbus Wheaton Club, and was actively involved with Camp Fire Girls and Boy Scouts groups in the area).

THE PARK OPENS

In 1995, Metro Parks formally opened Clear Creek Metro Park. At the time, it extended to 3,800 acres (almost exactly) and nearly all of it (all but about 100 acres) was forested. And almost all of it was designated as part of the Allen F. Beck Forest Preserve. In developing a master plan for the park, Metro Parks cut its cloth very precisely to the unique body that formed the Clear Creek Valley. Whereas other Metro Parks were planned around a philosophy that about 20 percent of a park should be developed for passive recreation (such things as hiking trails, fishing or picnic areas, educational facilities), whilst the remainder would be undeveloped and maintained only in terms of conservation and specific resource management needs, Clear Creek was going to be different. The aim for Clear Creek Metro Park was to establish a split much closer to 90-10, or even 95-5, not the traditional 80-20 split.

The reasons for this were dictated by the fascinating geography of the Clear Creek Valley and respect for a landscape unique in Ohio. The valley, with a massive bedrock of blackhand sandstone, was cut by the creek itself. Or rather, the valley was reshaped and re-cut as Clear Creek changed its orientation from a westward to an eastward flow. In pre-glacial times, the creek flowed to the west, and the valley was also cut by two smaller unnamed creeks. The waters of the original Clear Creek were dammed and halted by a glacial advance, either the Illinoian Glacier from 400,000 years ago, or an earlier Pleistocene epoch glacier. As the water rose, it overspilled eastward over the gap between the two smaller creeks and cut deep enough through the sandstone to merge with the smaller creeks and change their flow eastward. Subsequent glacial melting increased the volume of the flow and the current track of the creek forged the valley as we know it today, with its spectacular cliffs and ravines. Clear Creek runs for 23 miles from its upper headwaters west of Lancaster. The last 7 miles of the creek course through park land, before flowing into the Hocking River just east of the park.

ROCKS TELL THE TALE

Blackhand sandstone is a very porous rock, which has led to the valley’s steep walls and its many deep ravines. The steep sides of the valley and its ravines provide shelter from winds and from solar heat, and has led to microclimate conditions that provide unusual habitat for the area. Rhododendron Hollow, and the northwest limit of the great rhododendron plant, is one prime example of these microclimates at work. Another is the dense evergreen forests of hemlocks that dominate the cool ravines of the valley, and which provide further shelter from the effects of wind and sun on the habitat and climate.

The blackhand sandstone is exposed prominently in the park as cliffs, which in many places display characteristic weathering patterns, often described as honeycombing. These almond-shaped gaps or holes are caused by the erosion of so-called clay galls in the rock face, finer-grained rocks which erode much more quickly than the harder blackhand sandstone when exposed to air, wind and rain. The cliffs are often a light to dark gray color, but in parts, like at Written Rock, oxidization from the presence of iron and magnesium adds shades of red, yellow and brown. Written Rock, in the western half of the park, is a huge area of exposed sandstone on Clear Creek Road, which bears its name because of carvings in the rock. The earliest of these carvings is from 1875, (a name accompanied by the year), so basically it’s an example of 19th century vandalism. There are grooves in the rock of a more ancient origin, and these are believed to be polishing sites used by Native Americans to sharpen axes or other tools.

Another characteristic of blackhand sandstone is a propensity for weathering to create crevices, and also to create fractures, which in turn can lead to calfing of the rock. One such calfing, or sandstone slump block, as it is commonly called, resulted in a giant block of sandstone falling from the cliff along Clear Creek Road. Known as Leaning Lena, this giant slump block is more than 30 feet high and weighs hundreds of tons. Although it leans over Clear Creek Road and its ‘lean’ appears precarious, there is no danger of this megalith actually falling onto the road.

THE PARK GROWS

Since the park opened in 1995, more land has been acquired, including the additional parts of the Benua and Barnebey Center holdings mentioned earlier. The latest acquisition, in 2019, was an 80-acre tract known as Fern Gulley, already surrounded by the park on three sides. The park acreage is now 5,470 acres, making it the second-largest Metro Park (after Battelle Darby Creek Metro Park). Of this, 4,769 acres constitute the Allen F. Beck State Nature Preserve. More than 95 percent of the park is forested. The hemlock hardwood forests of the north-facing slopes of many ravines and along the creek itself, provide a dramatic green backdrop to Clear Creek even through winter. A hemlock forest with snow is a must-see sight. The park also includes Oak-Hickory and Appalachian Oak forest communities.

Aside from the hemlocks, other beautiful species of trees found commonly in the valley include tulip trees, Kentucky coffee trees, sourwood, pitch pine, wild plum, dogwoods, and sour gum.

WANDER THE TRAILS TO SEE THE BEAUTY OF THE NATURE PRESERVE AND ITS WILDLIFE

Because so much of the park is a dedicated state nature preserve, off-trail use of the park is prohibited, except within 50 feet of the creek. However, Metro Parks has created more than 12 miles of trails, some easy (along the creek), but much of it rugged in nature, which reveal the spectacular nature of the valley to the dedicated hiker.

A hike at Clear Creek is as rewarding for birdwatchers and plant lovers as it is for the fitness enthusiast. Clear Creek is the home to 20 species of breeding warblers and almost 100 species of other breeding birds, making it a treat for birders. Breeding birds include forest species, such as the wood thrush, scarlet tanager and cerulean warbler. Northern species, such as the black-throated green warbler, Canada warbler, blue-headed vireo and hermit thrush breed in the cool and dark proximity of the hemlock forests. Whilst more typically southern species nest annually in other parts of the park, including hooded, worm-eating and Kentucky warblers, plus the Louisiana waterthrush and yellow-throated vireo. More than 800 species of plants are known to grow at Clear Creek, including rare and beautiful species such as the yellow lady’s slipper orchid, pink corydalis, and the previously mentioned great rhododendron. The park is also home to more than 40 species of ferns, including the rare and endangered resurrection fern.

Picnic tables are available along Clear Creek Road at the Fern or Creekside Meadows areas. There is also a picnic shelter, with tables, grills and a restroom, at the Barnebey Hambleton Picnic Area. Fishing for rock bass, smallmouth bass and rainbow trout is available on Clear Creek at nine dedicated fishing stations. Fishing is also available from a dock on Lake Ramona.

This is one of the greatest articles on the parks yet. The history of Clear Creek is amazing. I’ve heard some of it over the years — this is the most comprehensive and detailed of everything I’ve heard. I’ve copied it and saved it for future reference. Thanks so much!

wonderfully informative article. thank you