Last month when we visited the vernal pool (see Blog post), spring was just starting to break free from the icy grip of winter, although this winter wasn’t so icy…! The salamanders and wood frogs had just awakened from their winter torpor, the fairy shrimp cruised silently under the water’s surface, and the resident birds were cautiously announcing the longer days with song.

But now, as April runs headlong into May, it’s all change. Even though the adult wood frogs and salamanders have long gone back to the forest for the rest of the year, the vernal pool and surrounding woodland teems with life. Birds practically shout at each other, completely ignoring my presence. A pair of wood ducks take flight as I approach, and a green frog squeaks on its way under the surface.

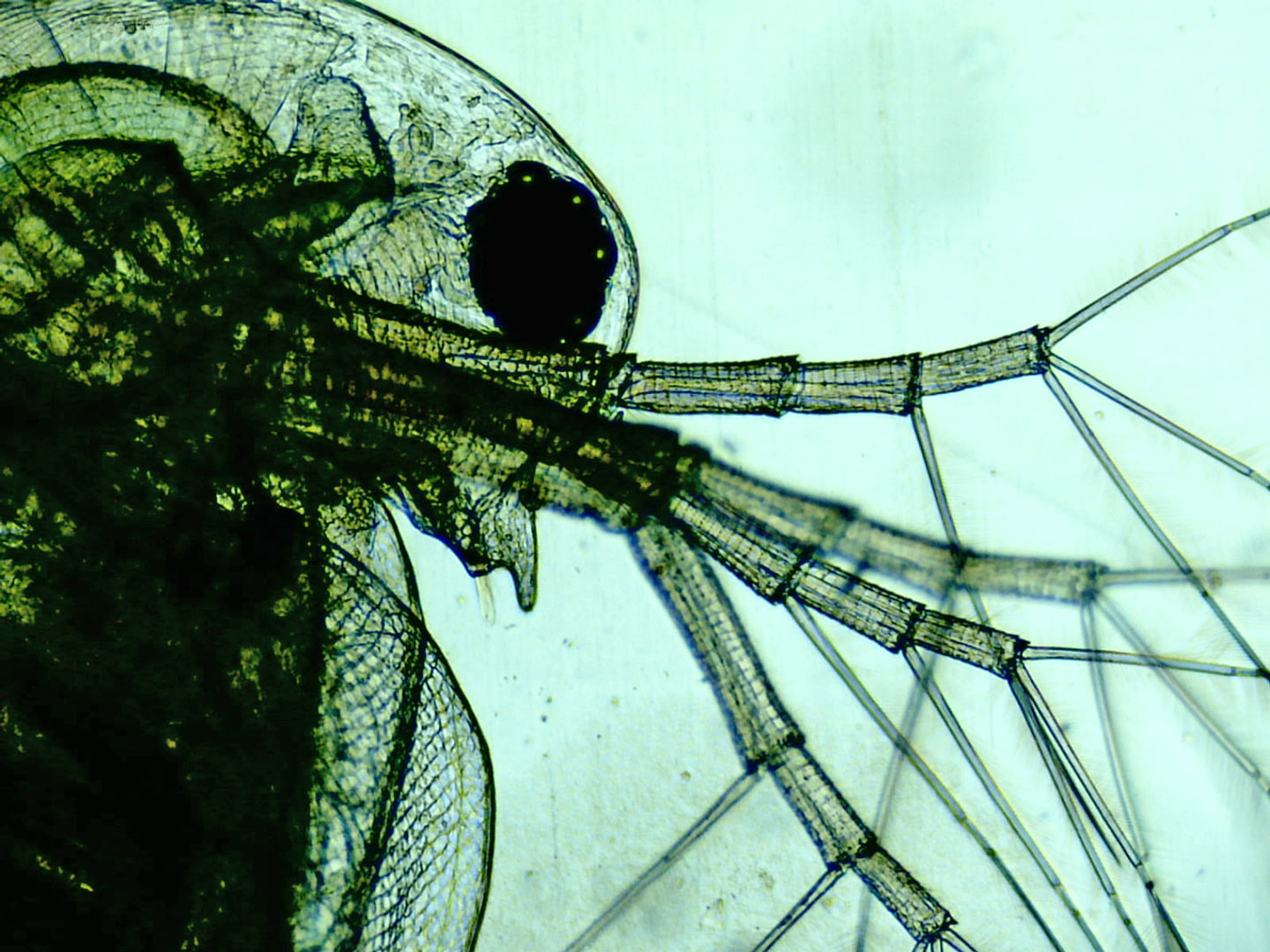

Peering into a sun dappled spot in the pool reveals a veritable soup of miniature invertebrate life. Daphnia, copepods, seed shrimp, little flecks of life almost too small for me to see without my glasses, as well as mosquito larvae! Lots of mosquito larvae! All of these are incredibly important menu items for the larger creatures in the pool, although the longer I stand in one spot, entranced by this underwater world, the more I feel like a menu item myself. It is at least a small comfort to know that the West Nile and other disease-carrying species of mosquitoes generally shun vernal pools, preferring puddles of water closer to human habitation.

As part of the monitoring process, I scoop some leaves from the bottom of the pool and take them to the shore for closer examination. I’m hoping to locate the offspring of those early spring visitors we observed last month.

I find larger invertebrates instead, backswimmers, predacious diving beetles, and alien-looking beetle larvae. All of these are predators of the salamander and frog larvae. I also found some aquatic isopods, water-loving cousins of those rolly-pollys (aka potato bugs, pill bugs) that you typically find under rocks in your garden.

I hit the jackpot on the next sweep of the bottom. Bingo! A three-quarter-inch spotted salamander larvae and wood frog tadpoles all in one scoop. They quickly shimmy under cover in my sample tray, trying to avoid becoming beetle snacks, even as I slowly remove the crumbling brown leaves for a good look at them.

What amazing creatures they are. The wood frog tadpoles are sleek, plump and almost black, nothing like their brown, masked parents we saw last month. It’s incredible to think about the change they will undergo in just a few short weeks.

I grudgingly haul out my glasses to check for development of back legs, the first pair grown by frogs, but I don’t see any yet. My captives bury their heads in a patch of algae, as if to confirm that they have a lot of growing to do in a very short time.

The salamander larvae are easy to tell apart from the frogs. On first glance, sans specs, they almost look like mosquito larvae—long and skinny—but the resemblance is only superficial. Those frilly things on the sides of the head are gills. And with the benefit of a hand lens, I see tiny appendages sprouting just behind the gills. Salamanders, in addition to having gills on the outside of their heads, develop front legs first. Unlike their vegetarian tadpole pool-mates, baby salamanders are all predator from the moment they chew their way out of the egg. Front legs are more useful for getting around and nabbing daphnia, copepods and newly hatched mosquitoes. And if the pool runs out of invertebrates before these bitty hunters transform? Watch out, bro! Salamander larvae have been known to turn to cannibalism.

There are so many invertebrates I haven’t found yet on this trip—fierce-looking dragonfly larvae, cadddisfly larvae carrying around their do-it-yourself leaf houses, and water boatmen, just to name a few. And of course the fairy shrimp are gone. The 64 degree water is too warm for their liking and they have already completed their very brief life cycle. But, my time is short for today, so I slide the creatures in my sample tray back into the water and bid adieu to the vernal pool until next month. It will by then have changed very dramatically again.

STEPHANIE WEST

Naturalist Sharon Woods